In Fallow Fields

by angeliska on November 28, 2013

The harvest has been brought in, and now we feast on the bounty of the earth – but how many of those potatoes waiting to be mashed were dug out of the ground by the same dirty fingers who will later wash and peel them? How many of the full bellies will have known what it is to be truly hungry? I ask these questions because I find myself thinking all the time lately about how we got to be where we are, and what came before. I have a thing about holidays – not just enjoying them (though I really do), but honoring the turning of the year, all that it brings, and all that it means. What it really means, underneath all the layers of sedimentary history, stories, old traditions with forgotten origins. It’s impossible for me to overlook the fact that Thanksgiving in this country is a bogus holiday built on the myth of friendship (and eventual betrayal, genocide, slaughter) between white settlers and the people who were here first. But before that story, there was an older one – a simpler one, about the ones who tilled the land, who gleaned the fields, who huddled close to the fire, to each other. I feel that we instinctively need our fall festivals, our moment of fullness before winter’s fingers dig in. It’s an ancient ritual, celebrating the abundance of the fertile earth goddesses, Ceres/Demeter/Isis/Inanna – and all the accompanying symbols come from what was sacred to those who practiced the old ways, in the old days, right down to the cornucopia. In Greek Mythology, the horn of Amalthea (she was the kind goat who suckled Zeus) became known as the cornucopia or horn of plenty. Before the frosts turn everything green and gold to gray and dun, we stop to pause and feel grateful for our stocked larders, our fattened pigs, our fields ready to lay fallow for a season. This is everything we worked for. Of course, in this current day, there has been a massive disconnect from that way of thinking, and many of us go through the motions: loading our carts in bustling grocery stores, stuffing ourselves, and merely enduring the company of our families. How to reconnect to that sense of belonging with the land, when almost everything we do is destroying it? I am curious if we will remember days of plenty so vividly when food shortages come to be widespread again. We used to live together, in tribes, in villages, in big groups. The old ones and the young ones, the strong ones and the fragile ones. We used to always be together like this, breathing each other in, listening to all the stories, working and living and loving and fighting and sleeping and waking. Now we live apart – connected by ether, but disparate, solitary. Some part of me remembers, though – what it’s like to lay sleeping on the ground, in a circle of other humans, firelight dancing on the cave walls. Curled into myself, but listening to the night sounds of breathing, whispering, a baby’s cry – and thinking, “This is how we are supposed to live – together. This is how it used to be, everywhere, for humans on this planet.”

I’ve been thinking about the wise old grandmother turkey I met recently, a grey and elegant crone named Chincha who lives on my friend’s farm. She is eleven years old, and mostly blind. She is friendly, though the other birds pick on her, because even with her still formidable size, she has grown weak with age, shrunken. Does Chincha know that the number one predator of her species is us? I never had met a turkey I liked and respected – though I suppose that really I had just never been properly introduced to any turkeys before. Will I still eat them? Yes, I think so – but I will be thinking of her bright black inquisitive gaze, and wondering if the bird on my plate had such spirit. I am a dedicated carnivore, but I do think about the creatures I consume – and I don’t know if that makes it better or worse. Both, I guess. I’m grateful for their gifts.

Before this week, I don’t think I’d ever known anything about the The Occupation of Alcatraz by Native Americans, or about Unthanksgiving Day (also known as The Indigenous Peoples Sunrise Ceremony), an event still held on the island of Alcatraz to honor the indigenous peoples of the Americas and promote their rights. This coincides with a similar protest, the National Day of Mourning, which began in Massachusetts.

“From November, 1969 to June, 1971, a group called Indians of All Tribes, Inc., occupied Alcatraz Island. This group, made up of American Indians relocated to the Bay Area, was protesting against the United States government’s policies that affected them. They were protesting federal laws that took aboriginal land away from American Indians and that aimed to destroy American Indian cultures. The Alcatraz occupation is recognized today as one of the most important events in contemporary Native American history. It was the first intertribal protest action to focus the nation’s attention on the situation of native peoples in the United States. The island occupation ignited a protest movement which culminated with the occupation of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation of the Oglala Sioux in South Dakota in 1973. Because of the attention brought to the plight of the American Indian communities, as a result of the occupation, federal laws were created which demonstrated new respect for aboriginal land rights and for the freedom of American Indians to maintain their traditional cultures.”

ALCATRAZ IS NOT AN ISLAND

“Before AIM [American Indian Movement], Indians were dispirited, defeated and culturally dissolving. People were ashamed to be Indian. You didn’t see the young people wearing braids or chokers or ribbon shirts in those days. Hell, I didn’t wear ’em. People didn’t Sun Dance, they didn’t Sweat, they were losing their languages. Then there was that spark at Alcatraz, and we took off. Man, we took a ride across this country. We put Indians and Indian rights smack dab in the middle of the public consciousness for the first time since the so-called Indian Wars…. AIM laid the groundwork for the next stage in regaining our sovereignty and self-determination as nation, and I’m proud to have been a part of that.”

– Russell Means (Oglala Lakota)

Photograph by Mitchell Kanashkevich from his series, JOURNEY THROUGH RURAL ROMANIA

If Chincha were a human, I like to think she would look like this woman.

Also, I highly recommend reading this today: IT’S DECORATIVE GOURD SEASON, MOTHERFUCKERS.

“In the Hollow”

I recently came across the incredibly powerful paintings of Michigan artist Andrea Kowch. Her paintings speak to me on so many levels: something about her fascination with those yellow fields, gray skies, the hard-bitten faces and floating hair of her women, staring sharply, consorting with animal visitors. I’ll let her work speak for itself, though:

“An Invitation”

“The Visitors”

“Sojourn”

“The Merry Wanderers”

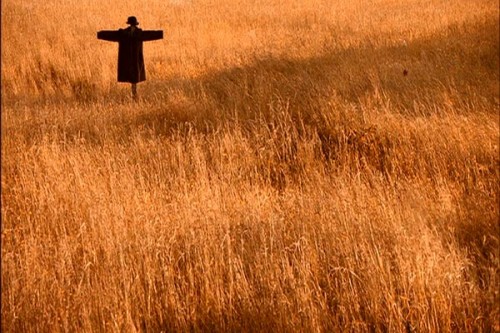

Much of what I wanted to share here began on a Thanksgiving a few years ago, trying to explain my love for eerie, slightly barren landscapes, and the art and films that take them as themes. Hungry outsiders lost in golden fields, haunting big white farmhouses, making bad decisions. I can’t leave any of that alone, it seems, so here it is again – expanded upon. Andrew Wyeth, Terence Malick, Philip Ridley, and now, Andrea Krowch – all making this art about a specifically American place and feeling – and it’s not entirely a good place or feeling. They all go there, though, again and again – wandering around between the rows, under that big horrible sky.

You see strange things hurl past you at high speeds on those backroads.

Faded signs whose obsolete messages you still struggle to make out,

beautiful abandoned houses, and dead trees that read as sculpture against

the big sky – black-limbed and bony, reaching up in agony with hundreds

of twisted wooden witch-fingers. I wish all the time that I could just bring them

all home with me to hang blue-bottles from. There’s got to be a way to do that.

I saw an old black limousine with bashed in windows parked in the middle of

a tawny cornfield. It looked like a lost still from The Reflecting Skin, and made

me think again of some of my favorite films that take place in the weird liminal

space that is a fallow field. They are all tied together in my mind – that one,

and Tideland, and also Malick’s Days of Heaven and Badlands. All favorite

films of mine, and all masterpieces of wrongness set in tall yellow grass

with decrepit old houses. A lot can happen in the terrifying wide open of

a prairie. That grass can whisper to you of terrible things. All of those films

come from this place, I think:

Andrew Wyeth. Christina’s World. 1948.

The woman crawling through the tawny grass was the artist’s neighbor in Maine, who, crippled by polio, “was limited physically but by no means spiritually.” Wyeth further explained, “The challenge to me was to do justice to her extraordinary conquest of a life which most people would consider hopeless.” He recorded the arid landscape, rural house, and shacks with great detail, painting minute blades of grass, individual strands of hair, and nuances of light and shadow. In this style of painting, known as magic realism, everyday scenes are imbued with poetic mystery.

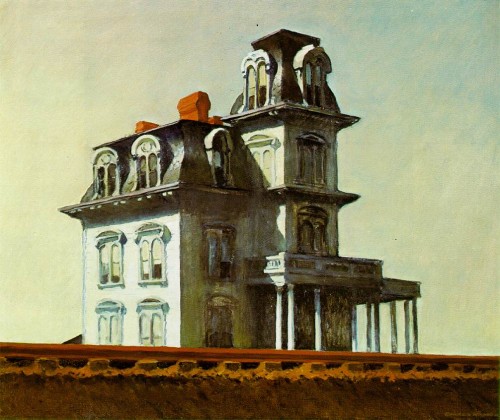

EDWARD HOPPER [1882–1967] – House by the Railroad, 1925

“Malick’s closest creative relative as an American artist may not be other filmmakers, but rather Andrew Wyeth, a realist painter who nonetheless offered such intensely studied, obliquely conceived pictures that they always seem to vibrate with a sense of hidden elements and forces. In much the same way, Malick constantly alchemises images into emotions, which is the very aspect of his films that remain hardest for the more literal-minded to grasp.”

– From Ferdy on Film’s piece about To The Wonder (which I still haven’t seen!)

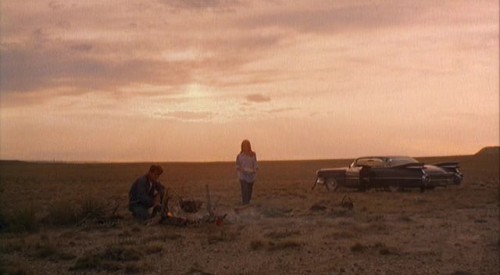

Badlands is one of my top ten favorite films ever. I love Terence Malick so much.

Oh Sissy. I love her because she’s brilliant, and I love her because she reminds me so much of my mom. In this still, she makes me think of Jeliza Rose, below – beautiful and precocious innocents dazzled by a strange and dangerous new world.

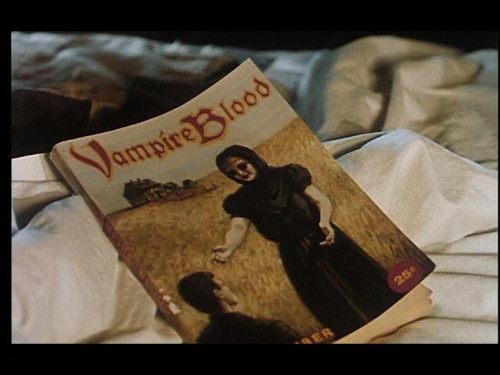

Tideland is reviled by many as being a pointless exercise in depravity by Terry Gilliam, but I loved it immensely. It is disturbing, and often uncomfortable to watch, but it is also beautiful and powerful. Most of my favorite films are a combination of both (see The Reflecting Skin, below).

The Reflecting Skin

“Like an irrational but beautiful dream, The Reflecting Skin unfolds with a clarity that’s disturbing. It’s a true American Gothic, a movie in which breathtakingly blue skies and Van Gogh-gold wheat fields are unlikely witnesses to the horrors confronting eight-year-old Seth Dove. For Seth, the world of childhood is one of nightmares in broad daylight: his friends are being senselessly murdered, his tormented father incinerates himself before his eyes, his half-crazy mother abuses him, his beloved brother returning from World War II is mysteriously wasting away, and the strange woman living next door must be a vampire.

Even with its obvious flaws, however, there’s something oddly compelling about this weird, weird movie. The Reflecting Skin may befuddle you by what it’s all about, but like a vivid dream, you’ll have a difficult time forgetting it.

Director Philip Ridley has stated that his film is heavily inspired by the paintings of Andrew Wyeth in its visual style.”

From NO MORE HEROES ANYMORE

Fall Plowing, by Grant Wood (1931)

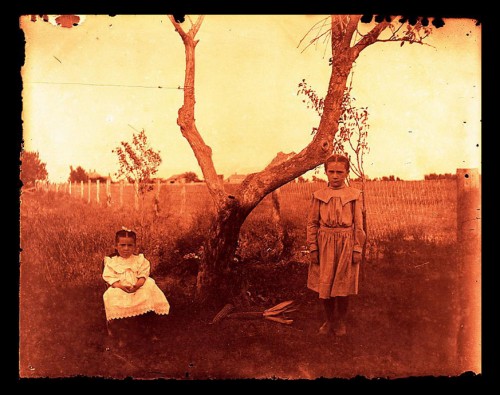

I honestly can’t remember where this is from.

Or this. But here they are. Happy Thanksgiving.

THE REFLECTING SKIN

BADLANDS

DAYS OF HEAVEN

TIDELAND

Related posts:

VULTURES + PERSIMMONS

Huexoloti Honey

Russet + Bone

Lone Grove Lullaby

4 comments

Thank you. There’s so much here to explore, and I thank you for that! Also, you put into words a lot of what I’ve been feeling about this holiday.

by Marta on November 28, 2013 at 11:28 am. #

Yes to all this, and I’ve been coveting the ‘It’s Decorative Gourd Season, Motherfuckers’ coffee mug.

by l.e.lake on November 28, 2013 at 7:56 pm. #

Wow, Finally someone else who feels the same way I do about eerie, desolate, barren landscapes and grey skies. As I was reading this post I was trying to remember the name of a movie that is part of this and saw it as I read further-Tideland. I did a paper in Art History on de Chirico that had the same feeling with deserted, melancholy and foreboding. It’s all part of this deeper darker, beautifully lonely feeling.

by Anne on February 6, 2014 at 2:41 pm. #

Interesting to note: three of these four movies were actually shot in Canada, in the prairie provinces. Deep in Southern Alberta, near the american border, for Days of Heaven. Crossfield Alberta for The Reflecting Skin, just north of Calgary. Saskatchewan, around Moose Jaw I think, for Tideland. Plus the end of Badlands was shot in northern Montana, just south of where Terry shot Days of Heaven. I’m from this region, and love all of these films (though my love for Tideland is less)

by K on October 12, 2016 at 2:02 pm. #